Colin Read • June 6, 2025

A Nation of Innumerates? - Sunday, June 8, 2025

This is a remarkable week. The debt clock displayed prominently in Manhattan, on the Bank of America Tower between 6th and 7th Ave. and 42nd and 43rd St., is within days of clicking over to $37,000,000,000,000.

That’s a lot of zeroes. But it means nothing to many, perhaps most people. Its relevance is only revealed when one divides it by the population of the United States, 341,817,979 residents or 112,888,022 taxpayers, to understand that we each owe $108,275 as our individual share of the national debt, while each taxpayer owes $327,758.

Many people have zero-aversion. I don’t get through the week without hearing some announcer or reporter confusing millions, billions and trillions. After all, that’s too many zeroes.

Physicists deal with numbers large and small in a very simple way. $37 trillion is just 3.7 times 10,000,000,000,000. And that very large number 10,000,000,000,000 is just 1 followed by 13 zeroes.

Same with the U.S. population. That’s just 3.4 times 100,000,000, or 3.4 times 1 followed by 8 zeroes.

People would be less confused if we stopped talking millions, billions, and trillions, and talked zeroes. I can easily divide 3.7 by 3.4 to get 1.08, and I can then subtract 8 zeroes from 13 zeroes to get 5 zeroes. That’s how I know the per-capita share of debt is 1.08 times 1 followed by 5 zeroes, or $108,000.

That's the way we used to calculate when we relied on slide rules rather than calculators. Ever since then, we have dummied-down by relying first on four-function calculators, then on PCs, and now on AI. Technology has encouraged the Great Dumbing Down, ironically enough. We don't do math anymore because few of us have to.

I know, understanding numbers very large and very small is tedious, but it is very simple once we understand a number followed by 13 zeroes or 8 zeroes or 5 zeroes is a big number. And while only Elon Musk can relate to a wealth of $300,000,000,000, we can all relate to a national debt per person of $108,000, for some the price of a house, and for others the price of a car.

So, it bothers me when I see commentators joke that they were never good at math, or it makes their head hurt, or they failed high school algebra. To me, that says they are bored or confused by the world around them, in all its immenseness, or the scale of wealth or poverty, human aspiration or destruction. Numbers mean something, and while we all aspire to avoid being illiterate, few harbor such qualms about being innumerate.

The problem is that even one who is illiterate can get the gist of a relevant discussion, but one who is innumerate simply gives up any attempt to understand large numbers. The innumerate among us simply trust those on television to interpret the scale of numbers for them, in what sometimes becomes the innumerate leading the innumerate.

It’s scary stuff when we give up on understanding the depth of our national debt, the number dying of starvation in Haiti, Mali, South Sudan, Sudan, and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, or that flying in a commercial jet is 200 times safer than taking the same journey by car. We can’t make sense of the world around us without basic competency in math, regardless of how proficient we may be with the English language. We can’t convey to others relevant numbers or statistics if our mind shuts down from zero disease.

The quality of our public discourse is not the only reason why we must overcome our fear of mathematics. Our economic future depends on it. The 25 best-paying college majors are all STEM - based on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. And yet, there is a growing shortage of graduates in the areas that have traditionally fueled economic growth.

Professors Hanushek and Wößmann of the University of Munich, in a recent paper entitled. "Education and economic growth," the authors show the dramatic effect of an improvement in K-12 test scores, especially in mathematics. Even a modest improvement in test scores, through additional investment in K-12 education and an increase in expectations, results in profound improvements in national GDP that is almost double the necessary educational investments. They show that a single generation (20-year) education reform package produces lasting benefits and increases a nation’s GDP by 36% over the remainder of the century. Given that China’s GDP is about a third lower than that of the US, such a difference in growth is the difference between which nation will hold the mantle of the largest economy in the world.

And yet, since Hanushek and Wößmann’s study was performed, math test scores have dropped dramatically in the U.S., especially following COVID. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Education is being disbanded, with a commensurate drop in billions of dollars of annual education investment. This is when every dollar of education investment produces two dollars of economic growth.

Now is the time to destigmatize mathematics, and turn our nerds into superheroes, much like the attitude that prevailed in the 1950s and 1960s when the West was shocked by the success of Russian engineers in first sending satellites and humans into space. Even today, Russia produces four times the engineering grads, while China produces eight times more than the U.S.

Don't get me wrong, though. Our citizenry must be literate, just as we must be comfortable with at least basic algebra. Nobody would admit they are comfortable with illiteracy. Nor should we be content to leave the understanding of numbers to others. Literacy allows us to communicate and exchange ideas. Mathematics allows us to comprehend the physical, medical, political, and economic world around us. Both qualities are essential for a well-informed society, and neither should be devalued.

By the way, what country scores the highest in the internationally administered K-12 math scores? China. No surprise. We don’t need to look much further than math attainment to imagine which economies will grow the quickest. Education investment worked well when the U.S. was in its period of ascendancy, but not so much for our disinvestment in its period of descendancy.

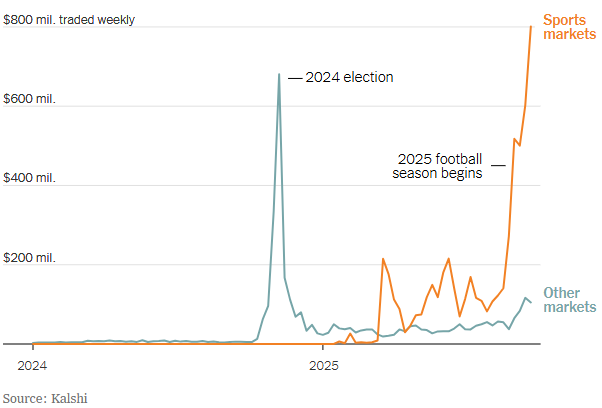

This is the 250th anniversary of a revolution in civilizations. In 1776 Adam Smith published his An Inquiry into the Wealth of Nations, a book that initiated the study of economics. His revolutionary book has since revolutionized how markets and entire societies operate. Not only did he define and glorify markets, but he heralded in the market for information and, with that, a democratization of ideas and of societies themselves. I realize these are bold claims that on the one hand seem quaint or trivial, and on the other hand seem simplistic in this age of cynicism and manipulation of democracies worldwide. Perhaps this is precisely the time to explain Smith’s aspirations for information and the inherent challenges therein. Smith’s idea was a simple one. If only we could rely on the collective wisdom of myriad citizens, in the marketplace for goods and services and the marketplace for ideas, we can become better informed collectively. In markets, one selling an inferior product or charging an excessive price will be priced out of the market and must strive to produce a better product for a more competitive fee. Likewise, our collective wisdom for better ideas and greater insights will encourage leaders to innovate and enhance civilizations themselves. The wave of democratization in the wake of the Age of Enlightenment applied to markets and democracies alike. We vote for better ideas and better mousetraps with our wallets, our ballots, and even our feet in our choice of where to live, what level of taxes to pay and what services we expect. We do so not because we are told or required, but because we exercise free choice in a fully informed marketplace for goods and service, ideas, and locales. Generations have been raised under Smith’s economic twist of the Enlightenment. Indeed, the U.S. Constitution and most all constitutions since then have embodied the truism that free markets and free choice create the best and most efficient way to organize peoples and economies. Indeed, entire industries were created to perfect Smith’s concepts. A free press, freedom of choice, property rights and the right to engage in commerce all flowed from Smith’s ideals, until now. These freedoms were based on the belief that every individual has equal access to good information and the ballot box and were just as geographically mobile as their purchasing power. For generations, free access to ballot boxes, markets, and information improved. Institutions were created that disseminated high quality information, and access to the democratic system consistently improved over time. At least until the recent monopolization of a media that increasingly concedes to political pressure, we could rely on the information we received. Likewise, until the popularization of social media, we weren’t inundated with poor quality information on the Internet that soon crowded out accurate information. In this world Adam Smith helped create, production and consumption, income and wealth multiplied, populations grew, and we even harbored the hope that wars would become obsolete. We have regressed. Markets are increasingly monopolistic and our choices have become more limited. We can no longer trust what we read, and financial fraud is increasingly common. Regulations and agencies designed to protect markets and citizens have been weakened or even eliminated. Trust has been eroded and cynicism is rampant. Meanwhile, production and innovation is being replaced by robots, artificial intelligence, and financial trickery. I shall describe a couple of instances of this regression. I begin today with a new phenomenon called “prediction markets.” They are an extension of bald-faced gambling, an activity that accomplishes nothing but consistent profits for the house. We tolerate gambling, and all its ill effects, as a price of economic freedom. We rationalize it as entertainment, despite the lives it may destroy. However, gambling in one sense is benign. After the house take of perhaps 10%, the rest that remains is a constant sum game, with winners equaling losers on average. Nothing is truly traded since no goods or services change hands. Such a waste of economic energy and productive capacity is tolerated so long as it is isolated. When John Maynard Keynes observed the excesses and then the ruin of Wall Street in the Roaring Twenties and its aftermath, he coined the term “animal spirits” to explain the irrational behavior of speculative markets. He likened it to gambling and questioned how it contributed to our collective economic welfare. Consistently rising prices in an overvalued market does not inform - it merely is good money following bad. In part II of this series, we shall explore the role of financial markets in greater detail. First we must dispense with the application of the notion of arbitrage to the marketplace for ideas. Such prediction markets are exemplified by Kalshi, but also characterize FanDuel, DraftKings, Robinhood, and other billion-dollar startups of late. Their modus operandi is the same. They give each of us the sense we can make money because we have more common sense than the rest of us. They will even often seed our first few bets just as a pusher might discount the first few hits of heroin. Typically, they only subsidize the first few bets on long shots though because they know longshots pay off at a lower rate than bets on the margin. That increases their return above their usual take. If you listen carefully, you will even hear Kalshi call such bets “trading”, even though nothing is actually traded but cash. There is no quid pro quo. Such bets do not change the course of a game or of the world events Kalshi allows one to bet against, except in the instances likely far more common than we might think in which the outcome of a game or an event is manipulated. People bet that President Trump would attack Venezuela (and won) because they had inside information the attack was mounting. Impoverished junior league and college basketball players unlikely to ever receive an NBA contract might throw a basketball game to collect a few thousand dollars at the price of their integrity. Hopefully such cheating and fraud is uncommon, but I fear it is far more common than we could possibly imagine Some might insist there is no problem with such cheating and insider information. However, in the wake of the Great Crash of 1929, an entire regulatory industry was created to return honesty to financial markets. The Securities and Exchange Commission was designed not only to protect retail investors like you and me, but also the integrity of an industry that depended on trust and honest dealing to raise money for innovation and production. In our infinite wisdom of late, it has been decided that we should oversee these new prediction markets with the same laxity as we oversee crypto. You may recall my recent “What Could Possibly Go Wrong” posting that expressed grave concern about regulation of digital currency by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission with the mandate to remove barriers to participation in whatever potentially fraudulent scheme that might come along. The foxes in the henhouse are left free to do far more than predict markets - they are increasingly shilling crypto, engaging in pump-and-dump schemes, throwing games, betting on insider information, and creating a sense of false realities, all with their profits in mind, at the expense of ours. Their "investments" do not change outcomes in the same way that buying a stock raises its price and augments the capital of a company so that it may expand. Such trades can enhance value but are also heavily regulated to ensure integrity. Prediction markets, betting on bitcoin, and gambling perform no such market purpose. In fact, such efforts more likely muddy the information waters. For instance, bettors in Kalshi state there is a 50/50 chance the US will experience more than 8,000 measles cases in this year. One to three children die for every 1000 infected, so there is even money on the death of sixteen children. I'd be more comforted if we spent more to convince people that holding back vaccinations kills our children rather than betting how many will not heed the warning of our experts. Betting about information such as that only dilutes the quality of information itself. Another example is the bias created by algorithms that run our news feeds. They make no attempt to provide us complete and balanced information. Instead, they feed us more of what has interested us. In essence, they magnify our biases rather than inform or ameliorate them. That's great for selling ads fueled by our anger and frustrations, but not so good at mending divisions and spurring useful debate across growing schisms. Such distortions for profit help explain the increasingly wide diversity of opinion over issues that are well-settled among experts and scientists. If we don't like the information provided to us, we can simply invalidate it as fake news. Opinion has replaced fact. Myriad regulations are designed to protect us from unscrupulous actors willing to deceive and distort. Automobile lemon laws aren’t promulgated solely to protect you from a defective car. Instead, regulators realize that, if lemons are tolerated, soon the market must price all cars as if they are all lemons and nobody will purchase cars at all. In effect, bad information forces out the good, just as George Akerlof described in his “A Market for Lemons” article that helped him win the Nobel Prize in economics. This is the greater risk. In an age of disinformation, for profit or power, we can no longer rely on what we read, see, or hear. Information is losing its value and, with it, the very premise that underpins the free market system. A quarter millennia after Adam Smith’s optimistic take, we are moving more rapidly than perhaps ever before in dismantling his assumptions that have endured for so long.

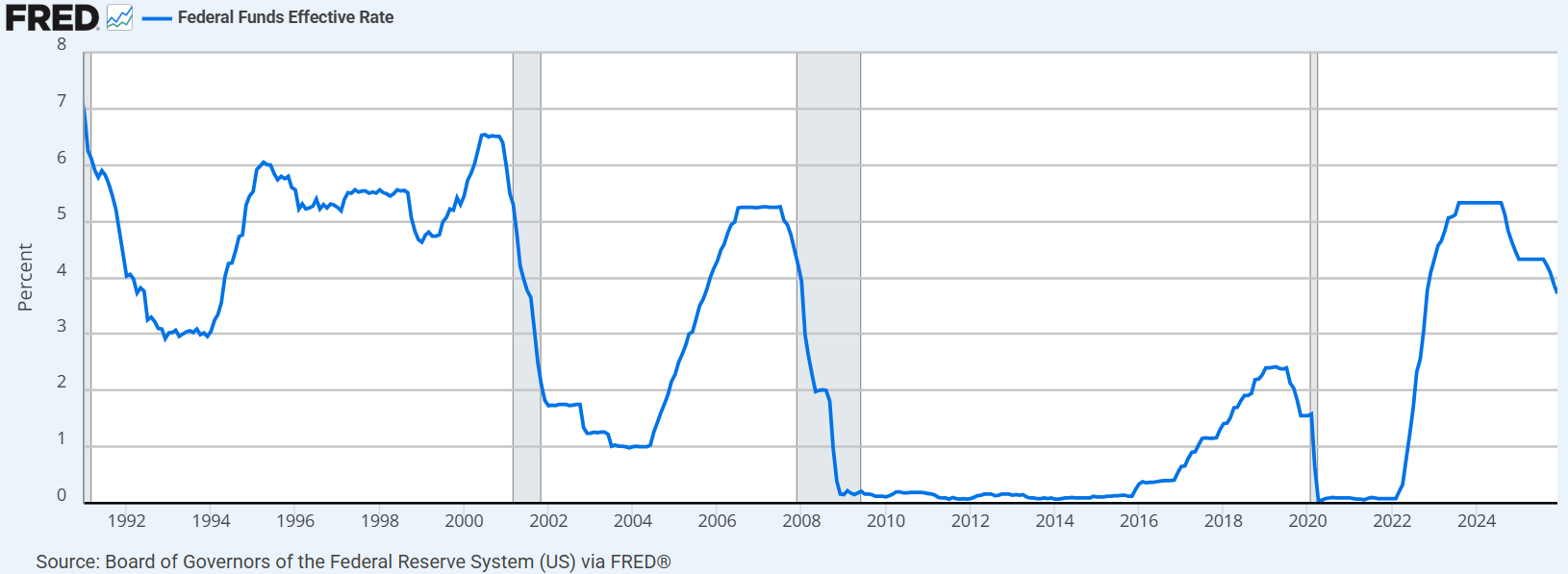

The shoe has dropped. President Trump has named his new chair to the U.S. Federal Reserve. The new chair shall be Kevin Warsh. That is a small relief. The current chair, Jerome Powell, was appointed seven years ago by President Trump in his first term. That appointment broke with tradition by giving the duty to lead the most influential economist in the world to a non-economist. No doubt Trump wanted someone then with more political savvy than the usual economics nerd. It appears that did not work out so well for Trump. He since realized that Powell was insufficiently loyal to the political whims of a president determined to bend the economy in the short term in his favor, damn the long-term consequences. Certainly, Kevin Warsh is a better choice than the name most commonly bandied about, Kevin Hassett. Born in Albany and a graduate of a Latham New York high school, Stanford University in public policy, and Harvard Law School, Warsh follows in the Powell tradition of policy and investment banking expertise rather than in the more typical economics expertise of past chairs. Warsh is an improvement over Hassett, the ultimate loyalist. If President Trump needed the most nonsensical argument for tariffs that nonetheless sounds good to 40% of the population, Hassett can come up with one. If the administration needs someone to appear on Sunday morning news shows to tell the nation the economy is in fantastic shape when it is not, Hassett is your man. He is able to pepper his argument with just the right amount of gobblygook to convince almost anybody who doesn’t know better that where there are big words, there must be wisdom. He doesn’t want to walk you through his arguments so you truly understand. Just trust the expert and don’t ask many questions. That’s perfect for today’s news cycle and attention span. Such an approach to appease politicians brings us back a century. Following a deep recession worsened by a wave of bank failures, J.P. Morgan gathered the nation’s biggest bankers in his Manhattan library and had his secretary lock the door from the outside. He told the illustrious captive audience that they cannot leave until they figure out what to do to prevent future bank failures. They agreed that the industry could no longer regulate itself and decided to request the federal government appoint a central bank that could control the money supply and the banking industry. It took a few years for Congress to get that act in order. The Federal Reserve was born on Dec. 23, 1913 to act as an independent body to safeguard the health of banks and the nation’s money supply. It was designed to be independent of Congress and the President in ways similar to the Supreme Court. Congress realized that politicians could not be trusted with monetary policy and their intrinsic desire to lower interest rates just before elections, damn the consequences. They appointed members for terms that span presidential terms precisely to avoid political interference. The Fed is also constructed as a non-profit, although any excess profits it generates through its operations can be turned over to the Treasury. And it has sole control over the interest rate it offers the nation’s federally chartered banks (and many state banks) who must borrow short term to prop up cash reserves. For its first couple of decades the Federal Reserve was not particularly effective. It certainly did not act sufficiently to prevent the bank failures that accelerated the downward spiral of the Great Depression following the Great Stock Market Crash of 1929. At that time it was running blind. There was no coherent economic theory for the money supply that could guide their work. Nor was there a macroeconomic policy for how to respond to deep recessions. These economic innovations would not come until John Maynard Keynes published his 1936 treatise when the Great Depression was almost over. In fact, the Fed did not become very sophisticated until the well into the aftermath of the terrible experience with inflation in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1990 the Bank of New Zealand adopted a policy to use its tools to keep their inflation rate in the range of 0% to 2%. The Bank of Canada, current Canadian Prime Minister Carney’s former employer, was the first large central bank to adopt a similar anti-inflation mandate first suggested by Keynes half a century earlier. Canada’s version of an inflation mandate policy soon spread to the United Kingdom and beyond. In 1977, the U.S. Fed had recognized a dual goal of keeping both inflation and unemployment sufficiently low ever since the stagflation debacle of the late 1970s. However, it did not adopt a “target” 2% inflation rate until 2012, two decades after other central banks routinely adopted this goal. However, once the Fed adopted this policy, it did so with evangelistic zeal. This policy has worked pretty well until politicians beginning with President Trump’s response to the COVID19 crisis used extreme expansionary fiscal policy at precisely the time when supply chains had collapsed. The Fed could do relatively little to mitigate such economic malpractice that President Biden continued into his term, but the Fed could have done more. In this blog I documented my frustration with insufficiently hawkish inflation mitigation policy by the Fed and Chair Powell over this unusual era. Powell and the Fed has since learned a lot about how to prevent runaway inflation that eventually cost Biden his job. To their credit, they have been balancing the dual mandate of low inflation and low unemployment ever since. Unemployment has remained in a comfortable 4%-5% range in the U.S., but any reader of this blog knows that inflation remains stubbornly above the 2% threshold. The proper economic response is for the Fed to increase short term interest rates it offers banks so that they are more reluctant to lend in ways that might fuel excessive spending by consumers and developers. In this way, economic activity declines a bit, which makes more difficult opportunities to raise prices. Inflation comes down, but at some expense to output and unemployment. All indications are that Kevin Warsh, the new nominee to the Fed chairmanship, is such an inflation hawk. He has of late been walking a fine line by speaking much less about his past preference of controlling inflation long term even if it is at the expense of unemployment in the short run. Instead, in his campaign to make it onto Trump’s dance card, Warsh has been increasingly of late emphasizing the job creation side of the dual mandate. That kept him in the running for a Trump nomination. From a pragmatic perspective, many hope that he will give just enough lip service to President Trump to keep him in the running for a successful Senate confirmation. After all, Trump nominates and then pulls nominations at a rate that we (used to) read paperback novels. Once he is in, his term will not end until 2033, well past the political pressure of this president and the next president’s first term. Hopefully that will leave Warsh to get inflation back in line and then begin to patch up some of the structural problems created by this administration’s abandonment of economic cooperation with its (former?) allies. I’m willing to keep an open mind about Warsh, even if I harbor concern that we need more actual economic expertise and a bit less political savvy on the Fed. While under ideal circumstances, a Fed that can move monetary policy in the same direction as the Congress’ fiscal policy would be great, most of us acknowledge that fiscal policy and Congressional sophistication has been an economic train wreck over the last decade or two. We are probably much better served if the Fed zigs as the administration zags. That is a terrible shame, I know, but it is a reasonable response to an incredibly irresponsible and incoherent national economic policy that has caused the national debt to quadruple over just two decades. These are complex economic matters and we must bring as much expertise and courage to bear if the Fed has a chance to right this ship. Knowing that the nomination could be far far worse, I retain a modicum of hope. Mind you, when in Greek mythology, Pandora, the first woman and the granddaughter of Zeus, reached into a forbidden vessel and releases almost all the world’s evils, such as sickness, toil, and sorrow, only hope was left lying in the bottom of the jar.

(Crypto Market Capitalization source: https://coinmarketcap.com/charts/ ) Most of you have probably not heard of a relatively obscure commission formed in 1974 to help regulate U.S. financial markets. You may hear more of it in the future. Farmers have a deep understanding of the ways of the world. They must be brilliant mechanics, thoughtful stewards of the earth, hydrologists and botanists, economists by nature who understand and live by supply and demand, and, with so much time for thought as they work the fields, great ponderers of ethics and morality. They also understand finance. Theirs is not a world of risk-taking because one risk too big can cause them to lose a farm held in the family for generations. Yet they must invest to seed a crop in the spring without knowing its price come harvest. They must also worry about drought and hazard insurance, but price insurance offers some budgeting comfort. For this price risk they have long relied on futures markets. Someone or some market that can pool risk across many farmers and many crops can offer to the farmer in the spring an expected future price for the crop in the fall. These financiers take on the risk and farmers agree to terms. Everybody benefits. This trading of futures markets was organized just so for generations through the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). Then, some smart financiers came along with brilliant new finance tools that allowed people to exchange price risk for many other markets beyond agricultural commodities - from foreign exchange to precious metals to oil and pork bellies. The great expansion of the CME meant that many more individuals could engage in such futures markets, often without the experience and knowledge of expert farmers and their financers. By the 1970s regulators worried that this burgeoning and broadening market needed oversight to protect unwitting investors against unscrupulous players flooding into futures. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission was formed to protect futures markets in the same sort of ways that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has protected you and I from other financial frauds for almost a century. Even then, the CFTC never really needed the power, nor exercise the control, of the SEC, until now, because trading of such futures instruments on the CME was still mostly by expert practitioners rather than retail small time investors like you and me. Then crypto came along. I’ve written a lot about the wild west of crypto, an intriguing set of new financial instruments that have no underlying intrinsic value from the production of some key economic good or service. Instead, crypto is really just gambling and speculation, with sellers of crypto believing an asset will fall in value or rise only slowly, and buyers purchasing these digital assets they believe will magically rise in value. It is fueled by the greater fool theory. Sure, some people actually exchange goods and services by paying with crypto currencies, but these transactional uses are far fewer than the speculative gambles. Shillers of crypto have tried to advertise every new coin that comes along as a great store of value based on all the wonderful things a coin can do. In other words, they were arguing crypto coins were financial securities. This implies they must come under the regulatory auspices of the SEC charged with protecting consumers from deceptive practices such as the "pump and dump" scheme often used to generate a buying frenzy in such crypto coins as World Liberty Financial, President Trump's coin. The SEC tried to regulate crypto to prevent an acceleration of the frauds we began seeing very soon after crypto became big. But, crypto bros are cowboys. They’d prefer the wild west to well-organized markets. It appeared that the SEC would fill that regulatory vacuum for a while, until the 2024 election. Up to 2024, Donald Trump was against crypto. But then the industry saw an opportunity. Crypto became the largest association of donors to the Trump campaign and to any candidate who promised to regulate crypto lightly. They even found novel ways to fund the Trump family. By creating new crypto coins themselves, the first family could sell these Trump coins through their new company called World Liberty Financial and a $Trump coin. The Trump family made billions selling crypto, and by offering access for crypto moguls for the price of millions and tens of millions of dollars a pop. The billions that flowed their way into the coffers of crypto-friendly politicians had a price. When Trump became president, he signed into law that the responsibility for regulating crypto would be that sleepy and light touch CFTC which nobody really cared about instead of the much more assertive SEC. Soon most all the members of the CFTC resigned. Meanwhile, since the 2024 election we see from today's graph that the value of the crypto industry has skyrocketed. Political donations by the crypto bros paid great dividends. With a new mandate of little or no mandate, an individual named Brian Quintenz was identified by President Trump to lead a CFTC devoid of commissioners. Indeed, had Quintenz been confirmed by Congress, he would have been the only member of the five-person Commission. The bylaws of the CFTC do not specify a quorum, so the prospect of having only one commissioner appointed by the President would create, in essence, a regulatory dictatorship at the very time it was being asked to oversee the entire crypto industry. Then, the Winklevoss Twins came calling. These very wealthy individuals made a small fortune by partnering with Mark Zuckerberg while at Harvard to form what eventually became Facebook. They took their winnings from suing Zuckerberg, plowed their millions into crypto to create a large fortune, and used a small part of their billions to fund the Trump campaign. When they realized President Trump was about to appoint Mr. Quintenz, they called in a favor. Quintenz was tainted in their minds by past CFTC investigations into one of their crypto enterprises which collapsed. The Winklevoss Twins wanted an even more zealous commissioner named Michael Selig, one who was expected to reduce fraud but also allow for exponential crypto growth, presumably through very light regulation ensured by a most friendly administration. After the twins lobbied the White house, Quintenz' nomination was withdrawn and Selig was sworn in a month ago, on December 22. Selig is now the sole CFTC commissioner - in essence a pro-crypto czar. I am guessing he is in no hurry to expand the size of the commission back up to its traditional five members. Instead, I expect we will see significant growth of crypto, with far more activity, new coins every week, and most certainly some spectacular failures at a pace far too rapid for one single czar to oversee. This is the ideal environment for an industry diametrically opposed to regulation. “Caveat Emptor”, let the buyer beware, should perhaps become the new calling card of crypto, to replace the “Fortune Favors the Brave” slogan from the $100 million crypto ad campaign that solicited Matt Damon as their front man a few years ago. There’s a saying amongst anti-corruption crusaders. Just follow the money. While regulatory bodies such as the SEC and the CFTC are supposed to protect the little guy, this new regulatory road is paved with gold and ill-intentions by those who profit handsomely from one get-rich-quick scheme after another. It’s too bad these roads seem to go right through the White House as a sleepy regulatory agency is repurposed into an avenue of riches for unscrupulous billionaire crypto bros. There may be some crypto purists who sincerely believe their digital coins will benefit the entire economy, but I venture that the huge profits bestowed on a few in this industry peddling Ponzi schemes, at the expense of millions of small-time dreamers, will show us once again the corrupting power of money and influence-purchasing.

In this third and final part of the series, I return to the original proposition that freedom is not free and ask what sacrifices we are willing to make to ensure our freedom also creates the opportunities we have come to expect from a modern economy. We cannot individually provide for ourselves all the opportunity to which many of us aspire. While we can individually take from a system of our collective creation, to what degree are we also willing to make our economic system as efficient and productive as possible? Various nations incorporate different demands on the individual in the creation of a vibrant economic system. The most significant dimension is in the investment we are willing to make in ourselves that are most conducive to sustainable economic growth. Today’s graph shows how different nations make different education decisions. Let me put forward a hypothesis. Citizens of affluent countries pursue our self-interest with little regard whether our decisions help or hinder national welfare. You may view that assertion as obvious. After all, aren’t capitalism and free markets based on unbridled self-interest? Adam Smith, the father of free markets and modern economics, actually thought otherwise. The book that represented his lifelong passion was not his famous “The Wealth of Nations” but rather “A Theory of Moral Sentiment. This earlier book asserted we pursue our economic interests with a sense of altruism. We want to do what pleases us by also advancing the happiness those around us. Smith was an advocate of what we now call “enlightened capitalism.” Certainly a few people make choices very much with the welfare of others in mind. Some others, such as vandals, relish in making choices that generate chaos and economic destruction. Most people probably act in ways in which we hope do no harm, but we don’t often make decisions designed to help others. This is plain old capitalism, not the enlightened variety. Fair enough. Some countries try to mediate our basic economic instincts by trying to guide the economy in ways which are better for us all in the long run. An example is education. In developed and aspiring nations, we all hope our kids will go to college. About 60% of Canadian kids attend, while 50% of American young adults do. That’s a good thing, although I have lamented in past blogs that we need more young people to attend technical college to learn how to build, wire, and plumb buildings and fix cars. Some nations, especially the high-aspiring ones, recognize that some disciplines fuel economic growth more than others. Let’s call them the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) disciplines, although many academics from other disciplines will argue otherwise. These nations encourage young people to become our next generation of technologists or inventors by subsidizing STEM studies. China, Russia, Germany, Iran, and India send 30% to 41% of their college students into STEM programs. Canadian students subscribe to STEM at a rate of about 25%, and about 20% of US students sign up for STEM. Countries from China to Canada subsidize and incentivize STEM to expand its graduates. The public policy argument is that, while higher wages in STEM fields is some incentive for students to study STEM, if a nation really wants more industry and innovation, it must adopt the subsidization of STEM as a national economic policy. If economic freedom also invokes opportunity, we must then accept that it is acceptable, even desirable, for each of us to do something for our country. We may not like math, but we should work hard at it in grade school so we do not preclude a career in science. Perhaps we should each be willing to perform some sort of domestic or international Peace Corp or a stint in the military at some time in our career. Or maybe we should feel a bigger obligation to volunteer in our community so we may share with others less fortunate what we enjoy ourselves. These are traditions that work well elsewhere. Many nations have compulsory service. The top five nations in today’s graph of STEM education attainment either have compulsory service or are contemplating reinstating it. And each of these nations actively encourage STEM education. Their rates of STEM education are strongly correlated with their economic strength and growth. Could that work in a country like the U.S. that does relatively little to incentivize STEM education? The U.S. makes available student loans for college education. It also offers grants for low-income individuals to attend college, although the total investment in grants is far smaller than the investment in Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers. But the U.S. does relatively little to direct students into the disciplines it needs the most to maintain the pinnacle of economic development. American policymakers are agnostic to the majors of college students. Our leaders feel that the State has no role in encouraging what Jane and Joey study. We remain indifferent to whether they study engineering or ecology, but economic growth is not indifferent. Perhaps that educational agnosticism is a luxury we can afford. But we should not delude ourselves into thinking such freedom of choice does not reduce future economic opportunity. Instead, we lament that the US no longer leads the way in the publication of academic research articles or the securing of patents, and we wonder where the innovators went and why manufacturing abroad utilizes higher technology than technology domestically. There is reason to be concerned. If students from a country like China graduate 41% of their students in STEM and the U.S. graduates 20%, let’s remember that China also has almost four times the population of the U.S. They graduate 3.57 million STEM graduates each year. The 820 thousand US STEM grads is less than a quarter of their total. India graduates three times the number of STEM graduates than does the U.S. We may try to console ourselves by arguing it is quality over quantity. Perhaps it once was. A couple of days ago the New York Times reported on the most recent study of university science quality based on research production - the Leiden Ranking of top science universities: https://traditional.leidenranking.com/ranking/2025/list. Harvard made the top 10 list, at the third position, and the University of Toronto made the 10th spot. The first and second spots, and the third through ninth positions are all in China. Of the top 25 science universities, the US holds three spots, as Johns Hopkins and Michigan join Harvard, and the University of Sao Paulo and Seoul National University make the top twenty-five, along with nineteen China universities. This shifting of academic fortune has mostly occurred over the last decade. Before President Trump’s first term when Chinese student enrollment in U.S. schools was dramatically curtailed, every faculty member would likely agree that the top students in our schools were often Asian. Now, relatively few Chinese students attend our programs, and we see an acceleration of scholars fleeing the U.S. to take up positions in China's top universities. Now, I know such a premise that we could do much more to maintain our relative position in global economic attainment is difficult to discuss or accept and often puts us in a defensive posture. I don’t mean to challenge anybody. I merely want us to meditate on whether we are willing to be pushed out of our economic comfort zone to attain the degree of freedom and opportunity to which we appear to have become entitled.

Last week we lamented that one can have freedom if completely unencumbered with the fruits and trappings of a modern productive economy. When given a choice, people would be willing to give up some freedoms for comfort and prosperity. It is difficult to have a lot of both freedom and property. A very productive economy with liberties and protections offered by government is the balance which many peoples choose, including those in Canada and the United States. Government is not inexpensive, but we can provide some amenities collectively that would be far more expensive for us each to provide for ourselves. Armies to protect our borders, police to keep us safe and courts to allow us to take advantage of the rule of law all permit us to specialize in our particular talents rather than fret over theft of our property. Of course, a government that provides everything will probably not be very efficient. In addition, there will invariably be products of other nations we may want to enjoy, but we cannot purchase their products if all we produce ourselves is domestic government services. Hence, an economy fueled solely through government spending is simply not sustainable. Indeed, a vibrant and sustainable economy depends critically on spending and production in the private sector. Unless there are an abundance of goods and services a nation produces which the rest of the world wants, healthy economies must depend primarily on its own consumption and investment. So, which one - consumption or investment? We establish an unsustainable balance between the two but we may find ourselves enjoying the party by consuming the seed of future prosperity. Economists know that investment may not only be small; it can even be negative. If our consumption depends on the production of things that depend on our human capital and machines, or the fertility of our farms, we will find production can falter if we do not at least repair our machines, invest in a modicum of education for our next generation of workers, and keep our farms well-irrigated and fertilized. If we do not make these investments, our stock of human, physical, and earth capital actually deteriorates, which is equivalent to negative investment. This is the metaphor of “eating our seed.” Of course, we cannot sustain an economy solely on investment either. People have to eat. Some consumption is necessary. The question is then to determine the optimal level of investment. Last week we noted that other economies invest far more than Americans and Canadians do. Canadian individuals and corporations invest less in financial assets and more in real assets. They also invest far more in American real assets (factories, farms, second homes) than Americans do in Canada. I just used the term “real assets.” That makes all the difference in whether an economy is saving for the future or gambling their future away. Let me explain. Increasingly in the U.S. economy our investments are no longer confined to homes and small local companies. As today’s graph shows, more than ever before and more than in any other nation, Americans “invest” in stock and other financial assets. These are paper investments. The stocks people find attractive to purchase do not result in greater production, more factories built, new innovations, except in the rare instance that the company actually issues more stock so they may expand. Such “public offerings” are relatively rare. Even in an unusual year, such as 2020 in which $435 Billion in public offerings were purchased, most of that capital raised simply went into the pockets of its previously-private owners, not in a rollout of new products or innovations. The actual amount of true investment, in the economic sense, is a tiny fraction of the value of the stock market. In other words, much of our financial wealth is not investment in the true sense of expanded productive capacity. It is merely the purchase of stock we find attractive from someone who doesn’t find the stock as attractive anymore. This is even worse for crypto “investments.” In that case, there is no product, no growing pie of potentially greater future consumption. In fact, not only is the economic pie not growing, the crypto pie shrinks because of fraud or entirely unnecessary electricity used to mint the bitcoin that fuels the frenzy. This is not to say that modern finance does not create some value. I am glad I am insured, and the constant scrutiny on companies surely keeps them honest and focused on expansion. Well-functioning financial markets tend to increase innovation and reduce the costs of risk, and these are good things. The price we pay for such innovation is unnecessarily high, though. There are other more efficient ways to expand production than to collectively participate in crypto lotteries or Wall Street beauty contests, as John Maynard Keynes so famously put it. So, why do we place such a disproportionate emphasis on wealth creation in financial markets in this country rather than by more tangible and productive investments pursued in other nations? More than most nations, for the longest time smart money and the huddled masses dreamed of coming to America. That consistent increase in demand each year ensured strong financial growth as more people bought into the American Dream. Stock markets grew faster than elsewhere because of this consistent growth even in the absence of true economic innovation. Add a dash of R&D and a strong public investment in university research, and we witnessed the strongest and wealthiest financial markets in the world. Who wouldn’t want to be part of such paper growth? This can be a house of cards. If values in an overinflated real estate market fall, like China is witnessing, there still remain homes people can live in or fields to farm. But when a speculative bubble bursts in financial markets, there may be little left but worthless paper. More than other real investments in today’s graph, much more of what Americans invest in depends on shared euphoria. We increasingly engage in a confidence game, with actual real investments a smaller share of the nominal paper investments that dominate the financial pages and business news shows. This is why national industrial policies are so essential. Leaving our future to beauty contests in an era in which coordinated scientific and engineering research and the need for greater public investments are so essential leaves us vulnerable and exposed to risk. This is how some major economies elsewhere are racing ahead. They develop policies and incentives that actually encourage more future production and create national infrastructures that sow the seed for future expansion. They emphasize the real side of the economy, actual production of goods and services, today and tomorrow, rather than paper profits through higher corporate valuations. They also recognize that the private sector cannot make such investment decisions alone. We live in an era of short-termism in which the fate of a corporate stock price rides not on what they can produce over the next few years but how they perform in the current quarter. Especially in the most affluent nations in which investing households live in relative comfort and financial security, we worry far less about saving for tomorrow than we do in consuming conspicuously today. These forces combine to raise the rate we implicitly discount the future and hence the return to some entity truly willing to invest in the next generation (or two). That is why enlightened governments provide the necessary incentives to shift spending away from present consumption and more into the technologies and sustainability of tomorrow. Households certainly do some of that by investing in their homes that provide services for generations. But the production sector needs to take its cues not only from Wall Street but from leading edge universities, visionaries, and insightful technocrats. We’ve addressed this week the greater need to emphasize true innovation and modernization of our means of production, and of investment in real property that we can still enjoy even if housing prices fall. I’ve left out perhaps one of the most important investments, our investment in our human capital. That’s the topic for part III.

In a song named for a receptionist at Kris Kristofferson’s helicopter base, he lamented to Bobby McGee that “freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.” Aye, there’s the rub. Citizens of wealthy nations aspire to be free. In the parlance of economists, freedom appears to be a luxury good for which we increasingly insist as our income rises. Wealth buys more luxury cars and demands more freedom. This is one reason why I am confident that aspiring but less affluent nations will establish more robust democracies over time. As income rises, people will demand it. There are also poor nations with freedom. If the income of a nation or a region is so small that it makes unattractive the seizure of power by tinpot dictators, people may loosely organize in ways that may offer a high degree of freedom in the absence of institutions that restrict their actions. They may be free of government oppression but perhaps not the tyranny of local bullies and thieves. Of course, if their income is also low, such crimes against property are probably insignificant as well. But, as wealth rises, we have more to protect. Hence, the Bobby McGee quote that we are most free when we have nothing others covet. We must put more effort into protecting our wealth from theft by others and that makes us less productive or progressive in other ways. One is not so free when they must live in well-locked homes in gated communities with private security. One must depend on financial institutions to secure their wealth, but that exposes them to financial fraud and digital theft. It is far simpler if one has nothing to protect. A wealthier nation chooses a balance between true freedom and the ability to generate wealth and income. In fact, some of the world’s wealthiest nations are also more restrictive. Other aspiring nations such as China are growing very rapidly under pretty heavy-handed government policies. If asked to choose between greater freedom and greater wealth, less affluent citizens of nations might choose wealth over freedom. But, as wealth rises, it augments happiness at a diminishing rate. At some point, we may sacrifice even greater wealth for more liberty. This is the basis of a consumption economy. Such economies, common in affluent nations, tend to be resilient because they are independent on the vagaries of international trade and investment. Domestic consumption is like the Energizer Bunny, powering on relatively autonomously. With consumption representing around 70% of gross domestic spending in the U.S. and around 55% of spending in Canada, economists can count in this self-sustaining economic force. John Maynard Keynes illustrated how such spending creates a virtuous circle of income generation. He noted that total spending in the economy is the sum of Consumption C, Investment I, Government Spending G and Exports less Imports, X - M. The net spending in each of these sectors contributes to additional flow of income for those from which spenders purchase. This upward spiral increases overall national income, as measured by Gross Domestic Production (GDP). Such a positive feedback loop is great so long as everybody does their part. Consumers must keep consuming and Investors must keep building new factories, designing new products, and creating new technologies. Should these forces falter because consumers and investors become fearful, as Keynes noted in the 1930s, an economy can degenerate into a depression. This is why economists pay so much attention to consumer sentiment and net domestic investment. An economy cannot be fueled solely on spending by the government on services. It must produce and sell things in the private sector. And if this private sector becomes more guarded and fearful, it reduces spending. In turn, the entire economy grinds to a near halt in a wave of fear and pessimism. This constant need to remain on the income generation path makes us a bit less free once we recognize the precariousness of modern free market economies. The positive feedback loop that generates greater requires robust consumption and investment. Unfortunately, if we ignore investment and instead simply try to enjoy ever greater consumption, we end up eating our seed. Investment is sowing some of the seeds from last year’s harvest into next year’s crop. The great New York State economist of a century ago, Irving Fisher, described how a sacrifice in consumption today by instead investing more of our income into expanding future economic growth. This is why a nation’s savings rate is so critical. By sacrificing a bit of consumption today by putting it away in savings, we make those dollars work by those willing to build new factories, design new products, or perhaps even educate a new generation of innovators. America’s problem is that its consumers have stopped investing in the nation. It has relegated this economic obligation in two ways. First, it has left to other nations a large share of new domestic investment. The dollars we spend to buy the products of other nations returns home in either domestic investment or the funding of government deficits. That is convenient for consumers in the short run because it allows us to temporarily have both strong consumption arising from low savings and also domestic investment that can sow the seed for future income. But foreigners do not invest in the U.S. economy, for instance, out of benevolence. They expect a strong flow of profits in the future. This return is repatriated to these nations to reward their consumers willing to temporarily invest in the American economy. In the long run, such repatriation of income reduces our economic vibrancy. The private savings rate in the U.S. has fallen to an abysmally low 4% of our income. This is entirely inadequate if the U.S. wishes to remain the largest and most vibrant economy in the world. We are eating our seed, or expecting other nations to provide our investment seed on our behalf, and we are sacrificing economic growth as a consequence. And we are spending a lot of money on educating our youth, but we have been unwilling to invest in that future as effectively as possible. As a result, our once-regular level of economic growth has fallen from a consistent 5% to a dismal 2%. Today’s graph shows the steady decline in growth that often exceeded 5% up until the 1990s. How can we get that economic vibrancy back? Well, in economics we say “there’s no free lunch.” It will mean making sacrifices today to create more investment and income tomorrow. Such painful solutions will require us to reduce some of the economic freedoms we have come to enjoy. We will leave these solutions to next week’s column.

This week the journal Foreign Policy published a 2025 retrospective. From their perspective it is not the state of the domestic economy that most troubles them. It is the failure to recognize the ascendancy of China following the first round of trade wars in 2018. I remember as a grade school child in the 1960s watching a video (we called them films then) of life in China. Small community pots would melt down scrap metal to make what was called pig iron. China in our mind back then was economically barely beyond the bronze or iron age. Japan’s economy was little more advanced. In fact, the term “Made in Japan” was pejorative. Now, it indicates products of high quality. My how have times changed. It is high time we revise our views of China’s economy too. Unfortunately, few North Americans have directly observed China's economic progress. While COVID-19 certainly shook up world travel, in 2019, the year before COVID hit, about 2.4 million Americans, 2/3rds of 1% of the population, visited China. In the same year, about 776 thousand Canadians visited, about three times the rate, at 2% of its population. While the US and Canada constituted the most non-Asian visitors to China, most North Americans travel elsewhere. China only ranks in sixth place for traveling Canadians. It does not fall into the top twenty for Americans. I mention this only because, if we do not experience cultures and economies abroad through our own eyes, we instead interpret them through others who often have not been to such nations themselves and who may have a political agenda. Our political narratives are often based on the history of two world wars and the Cold War after that. The Great War was one which forged the U.S. economic destiny. An ocean of conflict insulation meant the U.S. was not forced into World War I. While Canada fulfilled its obligations as an ally of the United Kingdom, and Canadian kids enlisted in droves from the onset, the U.S. did not formally enter WW1 until it was almost over. Instead, American factories churned out the armaments and airplanes to fight World War I, and reupped its economic ante to World War II for years before it was the last to enter that war. This meant that the U.S. benefited mightily from each war and built an economy of manufacturing scale that could not be mustered by allied nations. Japan, Germany, and China were simply trying to survive while America thrived. This left America as the only major economy standing as World War II ended and the Cold War began. In a YouTube video worth watching, Louis Vincent-Gave (https://youtu.be/RC8HVOPc2vM?si=HuAyDTCsedITuEMk) related a lament from German officers about American military power - “"One of our Tiger tanks is worth four of their Shermans, but the Americans always bring five." The sheer scale of the American economy won World War II and allowed the U.S. to dominate global economies for another half century. To cite these anecdotes is somewhat risky these days. We’ve been raised on a steady diet of American exceptionalism, cemented by successful moonwalks (Neil Armstrong and Michael Jackson), Boeing, the transistor, integrated circuit, Nobel-prize winning universities, cellphones, music and movies, and myriad other vehicles to export American innovations to a fascinated world. To assert that such exceptionalism was inevitable, given the size of the economy and the buying power of its large population is taken by some as contempt for American exceptionalism. But, with globalism, a concept America also championed at the conclusion of World War II, other nations now share in these successes. England revolutionized rock and roll in the 1960s, Volkswagen and Toyota became the world’s largest car manufacturers, Airbus now makes more planes and profits than Boeing, and we can’t buy American appliances or televisions anymore. The very nature of competition is imitation. Fosbury invented the flop but now all high jumpers use the same technique. All cars have cruise control and windshield wipers even though Cadillac championed them. An academic develops a new idea. If it is a good one, hundreds or thousands of her peers will take the idea still further. Competition should not be viewed as encouraging imitation, the greatest form of flattery, but should instead be viewed as raising the bar, just as the American Dick Fosbury caused high jumping bars to be raised every Olympics since the 1968 Mexico Games. Imagine how uninteresting bicycle racing would be if nobody but its originator was permitted to draft behind another stronger cyclist. Millions would die if nobody could successfully transplant a heart after Dr. Christiaan Barnard did so in Cape Town, South Africa in 1967. And certainly every nation watches closely the innovation of every jet fighter coming off the drawing board abroad. Some call such flattering imitation spying. As America loses its grip as the sole and dominant manufacturing and innovation nation, we have increasingly become guarded and accuse the innovation of others as a product of industrial espionage. At least at the political level, American industrial policy is now devoting an unprecedented amount of energy into the prevention of imitation rather than the creation of innovation. Now, there is a role for the State in finding the right balance of innovation. One of Britain’s and the United States’ gifts to the world is the firm establishment of property rights in the rule of law, in England through common law and in the U.S. through a constitution. This meant that we could all agree to a concept of private property that would be protected by the state so we can be gainfully employed instead of standing guard with a shotgun to ward off looters trying to steal our stash. Metaphorically, innovators could do what they do best with a modicum of patent protection, not to prevent imitation but to have the imitators share in the increasingly princely sums modern innovations require. The U.S. too played an early role here, not only in enshrining patent protection into constitutional principles, but also in championing bodies to preserve the rule of law internationally in the wake of World War II. The World Trade Organization, the World Court, and other international treaty organizations such as the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) attempt to create order and fairness in global affairs. Ironically, the U.S. and some other superpowers refuse to abide by such international conventions. What has all that got to do with China? A couple of things come to mind. First, as the U.S. abandons globalism, it leaves a vacuum in its wake that China is only too happy to fill. Their ascending global leadership will shift the equilibrium between nations for decades to come. Second, China learned well from President Trump’s first term that trade treaties mean nothing if a nation is willing to capriciously and unilaterally retract them. It learned its lesson in September of 2018 when President Trump’s first administration initiated a trade war with China. Following that episode, China invested massively in economic resilience. It developed huge new sources of sustainable power so it would be less dependent on American or global fossil fuels. And it banned the incredibly energy-intensive mining of bitcoin, which caused miners to flee to the U.S., and goes a long way into explaining why we now pay so much more for our electricity. In doing so, China created the least expensive new supply of energy of any major nation and gave its industries a huge cost advantage. Knowing it would have a scarcity of labor at some point, China developed a plan for automation to become perhaps the world’s most productive workforce. Compare two Tesla plants - one in Fremont, California (the world’s largest Tesla plant) and another in Shanghai. Musk’s China plant can produce each car with only half the labor of the U.S. plant. And each of these laborers earns less than 20% of their American counterpart. Musk pays more for health care of each American worker than the cost of an entire Chinese employee (who is also twice as productive). Such investment in China's economic transformation was expensive, as today’s graph shows. It was aided by a private savings and investment rate among Chinese citizens that is an order of magnitude larger than their American counterparts. It meant gutting wealth in the residential real estate sector, at great cost to their economy and people’s savings. And it required China’s society to buy in to this transformation for China’s economic resilience, a feat no doubt much easier given their political system. Twenty years ago the U.S. led in almost every one of 74 key technology categories. This year the Australian Strategic Policy Institute reported that China now leads in 67 of these 74 categories, including solar power, wind generation, battery technologies and state-of-the-art automobiles. For instance, Ford President Jim Farley recently observed that Chinese electric cars are a “major humbling force” because of their superior technologies and cost efficiencies. He noted they “pose an existential threat” if U.S. manufacturers can't compete, and that ceding the future of EVs to China isn't an option. His predecessor, Henry Ford, had a similar response to the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs that worsened the Great Depression. Ford was adamantly opposed to tariffs and their anticompetitive effect. All a tariff does is increase the price of one's competitors, which shelters the least innovative and encourages inefficiencies, all the while at the expense of consumers. Farley also said Ford Motor Company could not compete with Toyota and Hyundai in the small car market. Yet, there are tariffs on foreign cars Americans want but American companies won't produce. Let them drive pickup trucks, I guess. Nobody accuses Japan and South Korea of unfair trade practices. China did not create their superior in-car technologies, dramatically lower battery costs, or faster innovation cycles by cheating or stealing American ideas. They did so through a national plan to increase competitiveness, drive down costs, and enhance sustainability, values many North Americans share but without the ability to pursue ourselves, given tariffs and bans of efficient foreign cars. This industry is a metaphor for what China did in just the past few years while the U.S. increasingly turned toward trade wars. It would be irrational to assume that the U.S. can arrest China’s success simply by doubling down on tariffs. That will only make China redouble what has worked so well for them and so poorly for us. Instead, and as painful as that might be to our national pride, we should do what every country does when they see a superior technology elsewhere. Japan sought technology transfer by allowing American companies to build plants in Japan in the 1960s. Taiwan engaged in technology transfer in the 1970s, and China in the 1980s and 1990s. In a way to get around concerns that American-made F35 fighter jets they purchase may have built-in kill switches that could disable them if a Canadian prime minister offends an American president, Canada is now considering buying Saab Gripen fighter jets, with the promise that Saab would build them in Canada and enhance Canada’s aeronautical manufacturing sophistication. The point is that a nation does not become that “shining city on the hill,” using President Ronald Reagan’s metaphor, by building moats and tall walls. A great nation does not horde its magnificence nor trip up its neighbors. A nation becomes great by shining brightly, sharing its brilliance, spreading its wealth through generous foreign aid, embracing its allies and setting an example of liberty for its potential foes. It makes other nations become great too as they seek to emulate and engage a great nation so it too can celebrate liberty and prosperity. This may even require sharing innovations freely so others can innovate still further, just as academics share ideas so others can further expand the sphere of human knowledge. It is a mentality that, if we can make the global economic pie bigger, everybody’s piece of the pie will grow too. That is the concept behind economics, in contrast to those who instead believe they can grow their pieces of the pie by reducing the size of others. Economists have a fundamental faith that the world is a positive-sum game rather than a constant- or shrinking-sum game. Now, I know a prideful nation can be angry when past promises go unfulfilled and new generations are unable to share in the wealth of an illustrious past. The natural tendency is to lash out and blame others for an economy that is failing them. It’s hard to blame ourselves, so humans often blame the other - any other, from a different race, religion, nation, or culture. I understand the frustration. It must be validated and addressed. And I know that to take notice of China's success while competing American companies like Ford atrophy under a lack of a national industrial policy can be viewed as being a China apologist. However, if we are to return to the shining city on the hill that acts as a positive beacon for all to emulate, we must assess things realistically and objectively, rather than through arrogance, complacency, or hostility. It's not who "has the cards" but how we play the game. For my New Year's wish, I'd like to see the U.S. return to its past glory, and I'd like to see Canada, Europe, and others join it. What's your wish for 2026?

Some key economic data came out this past week that would usually warrant some comment. I am going to hold off on that until some more data comes out though because the consumer price information that was released remains a bit problematic. It was missing data from the previous month and seemed more timed to measure Thanksgiving weekend grocery discounts than a true measure of the economy. Nonetheless, it showed slightly improving inflation but with more significantly worsening increase in unemployment that is three times worse than the layoffs of federal employees. More on that later. Instead, let’s try to better understand the effects of tariffs by exploring one key commodity necessary for manufacturing items as varied as the cars we buy or the cans that hold the beer we consume. It’s not oil, sometimes called liquid gold. It’s solid electricity - Aluminum. There are a few industries for which electricity is such a prominent factor of production that their cost of manufacturing tracks electricity prices. One is bitcoin, in which about 90% of the cost of processing bitcoin transactions is consumed in electricity purchases. Similarly, Artificial Intelligence is highly electricity-intensive. Combined, these two processes are increasing electricity demand and raising the prices Americans pay to keep our homes lit and heated. Canadians have a bit of an advantage there because they have not allowed bitcoin mining to take hold as much as it has gripped US energy usage and politics. Canada is now identified as a good place for AI, though, with Microsoft recently announcing a $19 billion investment in new Canadian AI production and processing over the next few years. That investment is huge, given the size of the Canadian economy, and will surely move Canada up further from its 14th positions worldwide on the incorporation of AI into its economy. (The U.S. did not post in the top 20). One reason why Canada is becoming more central globally in such things as AI integration, cloud storage, and innovation is that it is blessed naturally with abundant sustainable electricity. Fully 80% of its electricity is non-greenhouse gas emitting, with about two thirds of its energy coming mostly from hydroelectricity. Such abundant electricity is cheap. The United States knows that. Today’s graph, courtesy of the U.S. Energy Information Administration, shows the very large imports of energy from Canada to the United States. While it costs a fair amount to build a dam or build out a solar or wind farm, once constructed that energy is almost free. This very low cost energy favors industries that rely highly on electricity. In addition, Canada has not squandered that electricity in ways seen south of its border. It resisted the big influx of bitcoin mines that inundated the U.S. once they were forced to leave China. Mainland China realized that they could make more money manufacturing the mining machines used worldwide than in being forced to burn more coal to mine bitcoin itself. The U.S. opened its arms to these miners, and its retail electricity users have been paying the price ever since. This leaves Canada with a distinct advantage in producing solid electricity - aluminum. Let’s for a moment discuss the role aluminum plays in Canadian manufacturing, how the U.S. benefits from this low cost and essential manufacturing commodity, how the new 50% tariff on Canadian aluminum is forcing up car, appliance, and beer prices for Americans, and how it is false to claim that Canada has an unfair trade advantage or is “dumping aluminum" in the U.S. market as President Trump claims. The world’s largest aluminum smelters coincide with those nations that can provide the cheapest energy costs - Russia, China, Canada, and Norway, for instance. In fact, Norway’s main facility is owned by a large hydroelectric conglomerate, Norsk Hydro, which is substantially government-owned. With abundant and cheap hydroelectric power, the small nation of Norway is an aluminum powerhouse because upwards of 60% of the cost of energy production costs are from electricity. Similarly, Canada is a world leader in aluminum production, primarily where there is the most hydroelectricity - British Columbia and Quebec. Just as South Africa can corner the market on diamonds, Boeing and Airbus can produce better aircraft based on their engineering advantages, and Saudi Arabia is a petroleum powerhouse, Norway and Canada can produce aluminum cheaper than just about anywhere given their endowment of energy. This abundant supply of cheap aluminum is also good for partners who trade with these nations. For instance, the U.S. is more industrialized than Canada and simply cannot make aluminum as cheaply as can Canada. Nor should they. If the U.S. tried to be aluminum self-sufficient, all its products employing aluminum would be uncompetitive, too much resources would be diverted to an industry that can never outperform, American consumers would lose out in higher prices, and American exporters would find other nations do not want to pay the price for their airplanes, as an example of a heavily aluminum-dependent industry. This is an example why a claim that Canada somehow competes unfairly because it can price its aluminum cheaper than other nations that trade with the U.S. simply makes no sense. Its comparative advantage in energy prices permits a lower price, not unfair competition. Canada is not “dumping aluminum” if it has a natural cost advantage in aluminum production, just as Canada does not “dump softwoods” just because timber land is so abundant in the world’s second largest country covered with trees. Similarly, Walmart is not dumping the goods it sells at a lower price just because it has a very efficient supply chain. To have 50% tariffs slapped on Canada simply because it can take advantage of its natural resources makes as little sense as if the world imposed a 50% tariff on SpaceX rocket services simply because it can launch rockets cheaper. In the end, economically unsound claims of unfair trade practices has certainly hurt Canada. But it also hurts those nations that depend on access to Canada’s inexpensive natural resources, especially the American consumer. Economists would take this argument still further. For instance, if China feels that it wants to subsidize its exports, that is equivalent to the Chinese government sending a check to American consumers. What is the problem with that, unless the goal was to so weaken competing U.S. producers that they are put out of business. I cannot think of many, if any, cases of such “predatory export pricing,” although I am sure that such ruthless competition occurs on occasion. In fact, the most common form of predatory pricing is actually between U.S. corporations within the U.S. - Meta swallowing up competitors or Microsoft making Internet Explorer so cheap that it forces competitors out of the market. In the end, if exorbitant tariffs force Canadian aluminum and softwoods to dry up, the U.S. will be forced to either buy more expensive aluminum elsewhere or divert its own precious manufacturing capacity into uncompetitive industries. It would also need to generate more energy and at high cost given its opposition to wind and solar, the high price of fossil-fuel electricity production, and the multiyear shortage of gas turbines. Either way, when international trade is harmed by false claims of unfair competition, it is far more likely that those who cry wolf will be left holding the bag.